Twenty five years ago this month, Tim Berners-Lee first proposed what became the World Wide Web. Today it is living up to its ambitious name, serving three billion people with many more yet to come. To mark the anniversary, we’re telling the story of those early days in this article and in our annual issue of Core magazine.

Core also explores several other overlapping anniversaries of 2014. It has been 20 years since the web’s popular explosion and the rise of Web commerce, including the launch of Netscape, Amazon, eBay, and many others. Fifteen years ago Japan rolled out the mobile web the rest of us wouldn’t discover until the iPhone era, while here we remember 1999 as the teetering height of the dot-com boom. That’s an anniversary rarely celebrated given the immediate aftermath. Lastly 2014 marks 10 years since the web’s popular rehabilitation following the crash, including Google’s IPO and the rise of “Web 2.0” sites like Yelp, Facebook, Flickr, and more.

Other important Web milestones coming up include the first demo browser, server, and Web site (December 1990), and the public release of the WWW code library so that anybody in the world could build their own browsers and servers (August 1991).

Reaching further back, 2014 will also mark the 45th anniversary of general purpose computer networks. The first connection was over the ARPAnet, between Douglas Engelbart’s laboratory at SRI and another node at UCLA. Such networks were built as transport for online systems like Engelbart’s NLS, which is a key ancestor of the Web. Another blog piece in @CHM remembers Engelbart and his work.

At the start of the 1980s it was hard to imagine that the Advanced Research Projects Agency’s (ARPA) Internet protocols would become the “one ring to rule them all,” with dominion over the earth’s wires and switches from national payment systems to smart refrigerators. They were just one of several experiments in how to tie different networks together at the lower plumbing levels, a process known as internetting.

In fact, as that decade’s bitter standards wars unfolded around which internetting standard should prevail, the Internet we use today was a scrappy but obscure David facing several Goliaths; Open Systems Interconnect (OSI), the lumbering official favorite of governments and standards bodies, and two proprietary systems from computing giants DEC and IBM.

But then David began taking steroids—in the form of us government cash. With infusions from the military, the National Science Foundation, and other agencies, and building on its loyal base of open-source hackers, the Internet started bulking up.

It didn’t hurt that the Internet had working hardware and software when its most serious rival, the European OSI, was still mostly vaporware tied down in endless committee meetings . . . or that the Internet was backed by tech-obsessed senator Al Gore. Internet protocols began to spread like wild-fire. Looking back, it’s clear that by the decade’s end the Internet had already won, even if most insiders didn’t realize it at the time.

Ad for adult services on Minitel, mid-1980s. France’s Minitel system was the first truly mass-market “web,” with over six million users by 1986.

But because the Internet was a non-commercial net used by geeks, nobody had bothered to write slick, easy-to-use online systems to run over it, such as Minitel, or CompuServe, or Prestel, or AOL, or LexisNexis. Those systems were proprietary, and mostly ran over their own networks. The geeks who traditionally used research networks like the Internet got by with an assembly of fussy tools only a power user could love. To grow beyond those core users, something had to change.

Who would put an online system on the Internet? Back in the 1960s ARPA itself had kick-started some of the world’s very first such systems, from timesharing to Doug Engelbart’s eponymous NLS (oNLine System). But the agency’s champions of these upper “user” layers—including J.C.R. Licklider, Engelbart, and Bob Taylor—had long since moved on.

So the vacuum above the Internet began to get slowly filled by a rag-tag collection of online systems written by lone wolf volunteers and open-source collaborations, some from within the freewheeling Internet community itself. There was Gopher, a barebones document navigation system from the University of Minnesota, and WAIS, a mildly commercial navigation system that worked somewhat like a search engine. Usenet, whose sprawling discussion boards had long hosted lively discussions on everything from sadomasochism to particle physics, was the only existing system to get adapted to the Internet. Another set of online systems featured hypertext, the clickable links so familiar today. These included Viola, from brilliant but bored Berkeley student Pei Wei; Hyper-G, a slickly packaged and very complete system by Austrian researcher Hermann Maurer, Lynx; and several others.

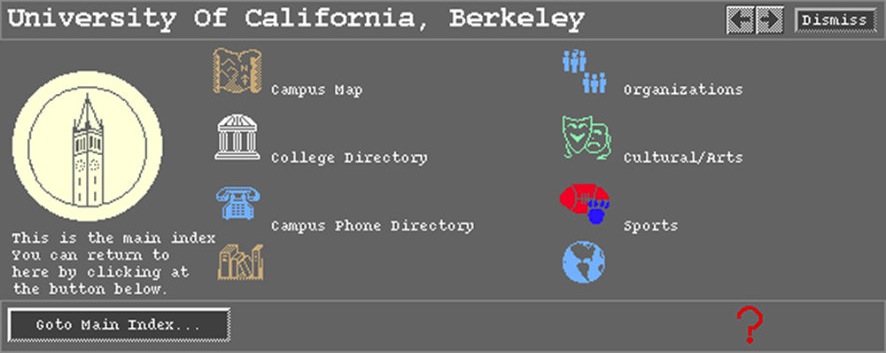

Viola hypertext system, 1989. Viola was a powerful hypertext system by student Pei Wei. He later turned it into an important early web browser. © UC Regents

One of the more obscure of the late 1980s attempts to create an online system for the Internet came out of CERN, the huge particle physics laboratory in Geneva, Switzerland.

The tiny project had a comically ambitious name: “WorldWideWeb.” Its main inventor, English physicist turned programmer Tim Berners-Lee created the web as a nearly underground project with help from colleague Robert Cailliau and their students and assistants, and without any official support from CERN.

Many of the people strongly attracted to hypertext share personality traits that could be labeled Attention Deficit Disorder: distractible, absentminded, and creative. To these folks, traditional hierarchical categories are numbingly predictable, the cyber equivalent of chloroform. But a clickable hyperlink can lead anywhere. It offers an intoxicating glimpse of what it might be like to make tangible your own fleeting thoughts and associations; to pin the butterfly of insight. In fact, the man who originally coined the word “hypertext,” Ted Nelson, may have co-invented the medium partly to compensate for his own troubles focusing.

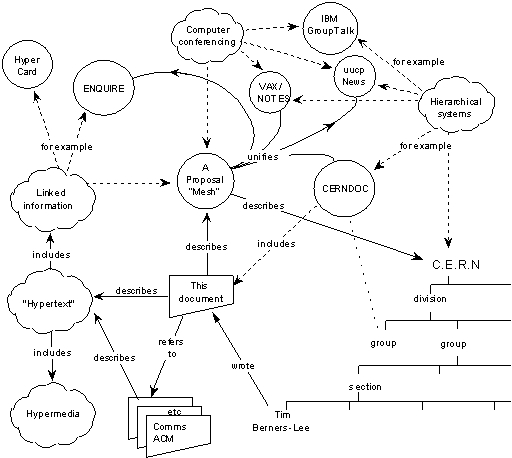

Diagram from “Information Management: A Proposal” By Tim Berners-Lee, CERN, 1989. © CERN

Passionate, fast-talking Berners-Lee has been described as a living hyperlink. The son of early computer professionals, he had come up with his own hypertext system nearly a decade before the web. The idea stayed with him through a series of contracts and a start-up venture, and by the late1980s had turned into an obsession. He mercilessly pestered his managers to send him to an emerging series of hypertext conferences in the late 1980s.

Most creators of online systems had started with a blank slate, without worrying too much about compatibility. From Engelbart’s NLS in the ’60s to Hyper-G in the 1980s, they had assumed their adopters would put in some effort just to get the system going; converting existing information to the new format, perhaps even buying custom equipment.

Berners-Lee and his colleagues could assume no such thing. The 1980s were a Babel of conflicting standards for both online systems and the networks that underpin them. But if there was one place that lived that chaos fully, it was CERN. Because it is funded by over a dozen countries, the institution not only had all the many competing standards of the era but also obscure national ones thrown into the mix, plus a bevy of home-grown contenders developed just for physics.

The result? The hypertext-based WorldWideWeb had to work within the mix of existing systems, document formats, and databases—instantly. It was the first time realpolitik and the daily needs of users had been coupled with the hypertext vision to “make sense of the madness” in his words, rather than try to replace it.

Berners-Lee’s idea of how information would appear to web users was a rudimentary version of the elegant visions of earlier pioneers. But his “viral” idea of how the system could spread—user by user, system by system, from the bottom up rather than from the top down—was based on Internet culture and was rare among online systems. The only competing system that developed similar viral hooks was Gopher, which could well have beat the web if not for some bad luck.

Over a couple of months in the fall of 1990, Berners-Lee’s boss Mike Sendall pushed him to finally create prototypes for the main elements of the web we know today. By Christmas, Berners-Lee had URLs for addresses, HTML for pages, HTTP for links, and a web browser. Most remarkably, his prototype browser was also an editor; you could author web pages as easily as in a word processor.

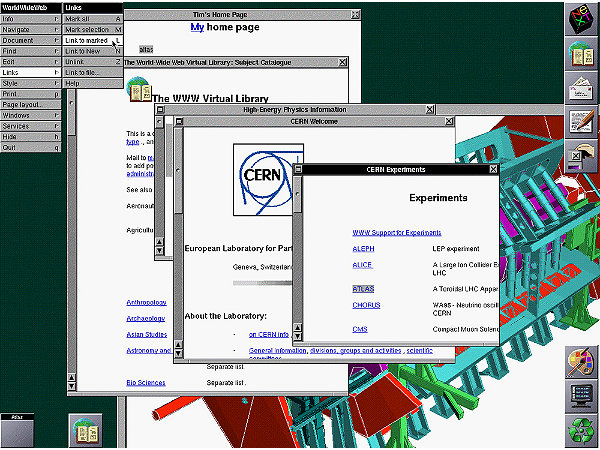

WorldWideWeb browser-editor, ca. 1992. Developed in late 1990, the first Web browser was also an editor for creating a personal “web” of linked documents. @ CERN

This editing feature was a pivotal part of his vision for the web; not only to be able to read information anywhere in the world, but to be able to contribute to it, and make references to anything, anywhere, in your own personal notes and to-do lists as well as shared documents. His hope was that a web of knowledge—perhaps even a “world brain”—would gradually assemble itself from the millions of links made by users in the course of their everyday lives.

The web was born.

The next year was perhaps the richest creative period in the web’s early development as Berners-Lee, Cailliau, brilliant programmer Jean-François Groff, and a growing circle of students and colleagues fleshed out a vision, which included a number of features yet to be implemented in the web today.

As a hypertext system the web was stripped down, even crude—something the close-knit hypertext community was not shy about pointing out. But the web’s design was also fumbling its way toward another goal. From his first Enquire system a decade before, he had been interested in using clickable links as not simply a convenient navigation.

Made for readers, but a way to map the real-world relationships between people, and projects, and ideas, and things.

Once mapped, those relationships could be read— and refined—by computers as well as people. This opened up possibilities for the kind of machine-aided pre-digesting of raw information that could in theory make all the knowledge in the world truly accessible. A decade later, Berners-Lee would flesh out these inchoate ideas into his vision for a “Semantic Web.” It was the kind of soft artificial intelligence approach outlined by Licklider 30 years before.

But there was an elephant in the room. Berners-Lee had written his elegant browser-editor on a powerful but rare computer built by Steve Jobs’ next Inc., known for its rapid prototyping features.1 The same work on a more conventional machine might have taken over a year. To demo the web on other platforms he’d had Nicola Pellow create a simple text-only browser. But for the web to grow, proper graphical user interface (GUI) browsers were now needed for PCs, Macs, and the UNIX workstations common in computer science. CERN refused to fund that development, which upper management saw as a stretch for an organization whose real job is smashing the building blocks of the universe to see what makes them tick. The project was stuck.

So Berners-Lee and Cailliau took a leap of faith that was both desperate and hopeful. They had Jean-François Groff create a library of ready-to-use web code, like a roll-your-own browser kit, along with a standardized server. Then they put out an appeal, asking volunteers from the budding web development community to use that library to write the needed browsers.

The response to the web team’s cry for help was fast, and heartening. Pei Wei converted his Viola hypertext system into the first web browser beyond CERN, followed by a number of others. Viola and Tony Johnson’s Midas laid out the familiar features of a browser we still use today. For the web team at CERN, it felt like a barn-raising; talented volunteers from all around the globe pitching in and meeting and chatting on the www-talk discussion group. But however beautifully conceived, these were one-man or student efforts; unpolished side projects that frequently crashed and could take even an experienced programmer part of a day to successfully install. The next volunteer browser changed all that. It was called Mosaic, and it was written in early 1993 by prescient student Marc Andreessen and UNIX programming guru Eric Bina at the National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA). At first it sounded like little more than a me-too browser in the model of Viola and Midas. But NCSA had been a major site in the 1980s’ expansion of the Internet, and had created and distributed the most popular program to run over the Internet so far, NCSA Telnet.

Recognizing the web’s potential, NCSA software manager Joseph Hardin quickly assembled formal teams for UNIX, Mac, and PC browsers as well as a server, and he and NCSA Director Larry Smarr turned the ignition key on the institution’s formidable support and PR machines. The result? The first web browser that was properly tested, supported, and easy for non-geeks to install. Like the Viola and Midas browsers it was modeled on, Mosaic left out editing; you could browse web pages but not change them. But Berners-Lee was confident that could soon be added back.

Soon journalists from around the world were virtually camped out at the Oil Chemistry Building where the Mosaic team worked. NCSA’s ever-expanding server rooms strained to keep up with the deluge of copies of Mosaic downloaded daily. Andreessen and Bina’s “What’s New” page became the front page of the infant web.

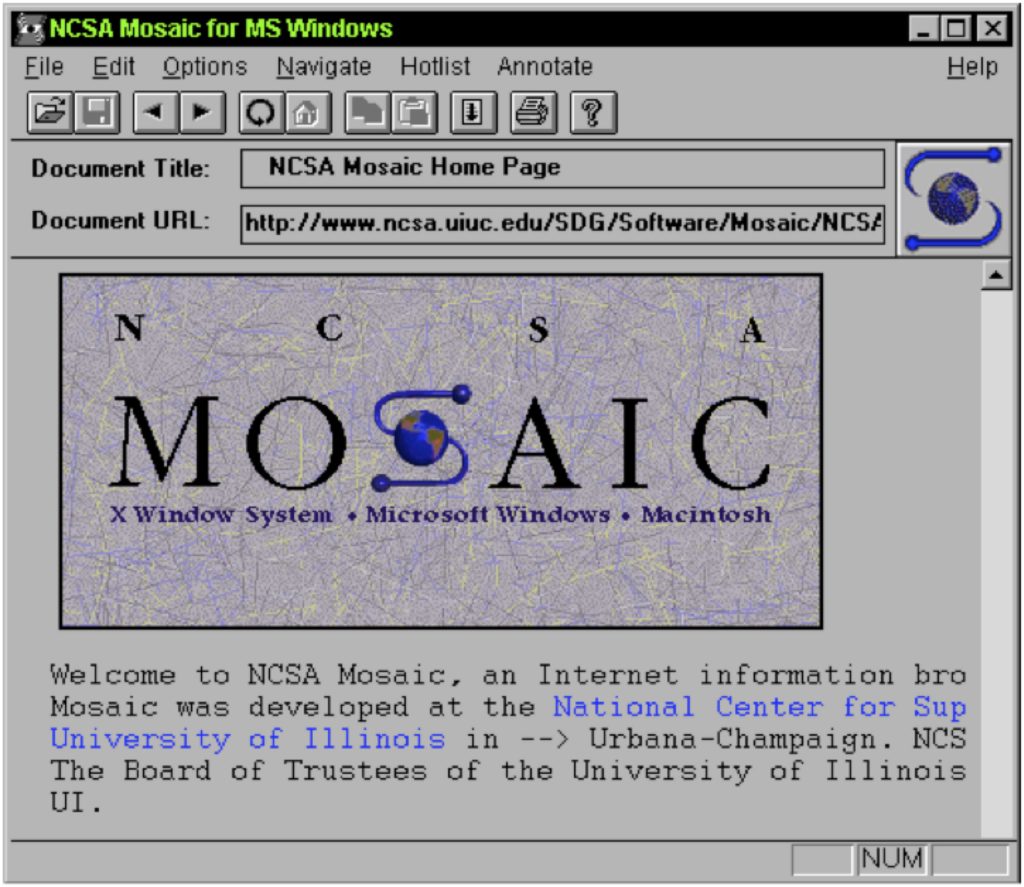

The home page of Mosaic, one of the first public web browsers.

Suddenly, the whole web community was riding a delicious wave of success together. To pioneers around the world, the late-night dreams of lonely years suddenly seemed not just possible but likely; whether your personal vision of cyber-utopia was an infinitely linked library, or a world brain, or a global marketplace. It was perhaps like the excitement in the early auto or radio industries, but now on a time scale compressed from years to months.

But with success came things to fight over.

There had already been tension between Andreessen and Bina and the core of the web community over the casual way they added simple in-page graphics to Mosaic, ignoring Berners-Lee and Cailliau’s long-term multimedia plans. The graphics proved hugely popular.

Mosaic’s success also created tensions over credit and control between NCSA and the CERN web team. In fact, much of the world came to know the web not as itself, but under an alias, as Mosaic. NCSA called its generic web server a Mosaic server, and its marketing materials never mentioned the W-word.

But the bitterest break was between the young Mosaic programmers and NCSA management. Each side felt the other was expendable, while their own efforts were the crux of Mosaic’s success. The programmers noted that they were paid student wages and given little credit for the product that through their drive and vision was making NCSA world famous. Management was convinced that without institutional support, Mosaic would have remained little more than yet another interesting but obscure amateur browser.

Marc Andreessen quit NCSA at the end of 1993 and took a job at pioneering Internet company Enterprise Integration Technologies (EIT) in Silicon Valley. Jim Clark, wealthy founder of Silicon Graphics, recruited him to help start a web company. Andreessen suggested a “Mosaic Killer” browser and server. They threw down the gauntlet by poaching half the Mosaic team from NCSA, including co-author Eric Bina, and the whole group founded Mosaic Communications (later Netscape) in early ’94. Despite a lawsuit from NCSA and commercialization efforts with Spyglass Mosaic, Mosaic was dead within a year—the loser of Browser War I.

Fast, slick, and offering full commercial support, Netscape Navigator was the browser that brought the web—and the online world—to the rest of us.