For fifteen years I documented the efforts of a secretive tribe of engineers, entrepreneurs, and venture capitalists in Silicon Valley as they created technology that would change our culture, our behavior, and challenge what it means to be human.

My project began in 1985 when Steve Jobs was forced out of Apple and began his quest for redemption by attempting to build a super computer for education. Steve represented the freewheeling sensibility of the times, combining his idealistic, hippie vision and design aesthetic with the space-race ambitions of the prior generation. I wanted to understand his process of innovation and believed that by photographing Steve I could also gain insights into the larger subject of Silicon Valley itself. I requested special access to shadow Steve and his team and he immediately agreed. After three years, I expanded my project, gaining the trust and private access to every major innovator and over seventy companies, often for years at a time. I continued shooting through the rise of the Internet and dot-com boom of the 1990s, generating 250,000 negatives over the life of the project.

During this era, the accelerating pace of innovation was affecting the very nature of work, the structure of corporations, and the global business environment as whole countries began manufacturing new technology. A digital revolution was underway that would create more jobs and wealth than at any time in human history.

Throughout the project I photographed with several concerns in mind:

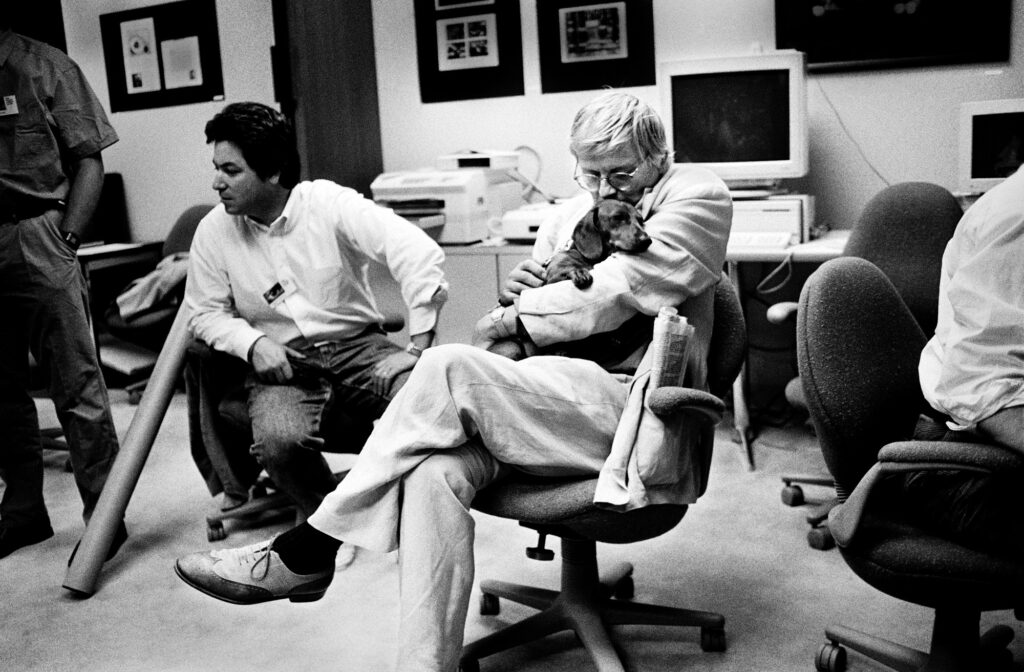

“The Painter David Hockney Rests during the First Photoshop Invitational.” Mountain View, California, 1990. © Doug Menuez/Contour by Getty Images/Stanford University Libraries

Primarily, I needed to understand how Silicon Valley innovators fit into the context of my ongoing work—I am often drawn to explore the human experience of individuals as they attempt to achieve the impossible, overcoming fear and limitations. I’m curious about what motivates some people to rise against insurmountable obstacles and find meaning in their lives, while others simply cannot engage. Steve Jobs was attempting to change the world with his team—to achieve the impossible, again—by fitting the power of a mainframe into a one-foot cube. Steve’s story was extremely compelling and drew me into his world. He told me he hoped a kid at Stanford could use it to cure cancer in his dorm room. Because he believed this was possible, his team also believed, and his pursuit became a noble mission. I began to see that technologists were like any other human beings working to overcome adversity. Except if they succeeded, all humanity might benefit.

PALO ALTO: NeXt CEO Steve Jobs and Susan Barnes, NeXt VP and CFO, reacting to a joke tod by an employee on the bus going back to the headquarters in Palo Alto, CA. The team was visiting the unfinished factory in Fremont in March 1987. (Photo by Doug Menuez, Contour by Getty Images)

I wanted to show the daily lives of the engineers, capturing moments of interaction and also to interpret the work environment, which was ostensibly dehumanizing. I sought to capture the context of this environment, looking for patterns of human behavior and emotion. I paid particular attention to any exhibition of stress, which increased over the years. This was in contrast to the public face projected by tech companies, which tends to be a polished veneer of extreme competence.

An early perception was that the tech world was building machines that would erase human imperfection. They seemed anti-human in nature. But when Macintosh appeared a new path opened. Doug Engelbart’s humanist vision, first posited in the 1950s, was invoked by the Mac’s user-friendly interface. Engelbart believed that computers should augment our brains, as opposed to the idea that sentiment machines would replace our brains with Defense Department funded Artificial Intelligence. A subtle but crucial debate had begun in the Valley. I included a consideration for the moral and practical questions being raised. Choices were being made for us about how computers would evolve that might ultimately impact the future of the human race.

Thinking on one level like a visual anthropologist, I gathered data about their behavior that others might decode later. I was very interested in the development of a unique technology culture and various subcultures such as “geeks” and “hackers.” There were the socially immature but extremely smart programmers with their Star Wars toys, writing code at 3 a.m., and the multitasking marketing and management people with their new flip phones and Daytimers. There were the instant millionaires and billionaires driving exotic sports cars and the hippie engineers. There were a few women and minorities, mostly found on the assembly lines, and some illegal immigrants. There was even a gay pride organization being formed called “Digital Queers.”

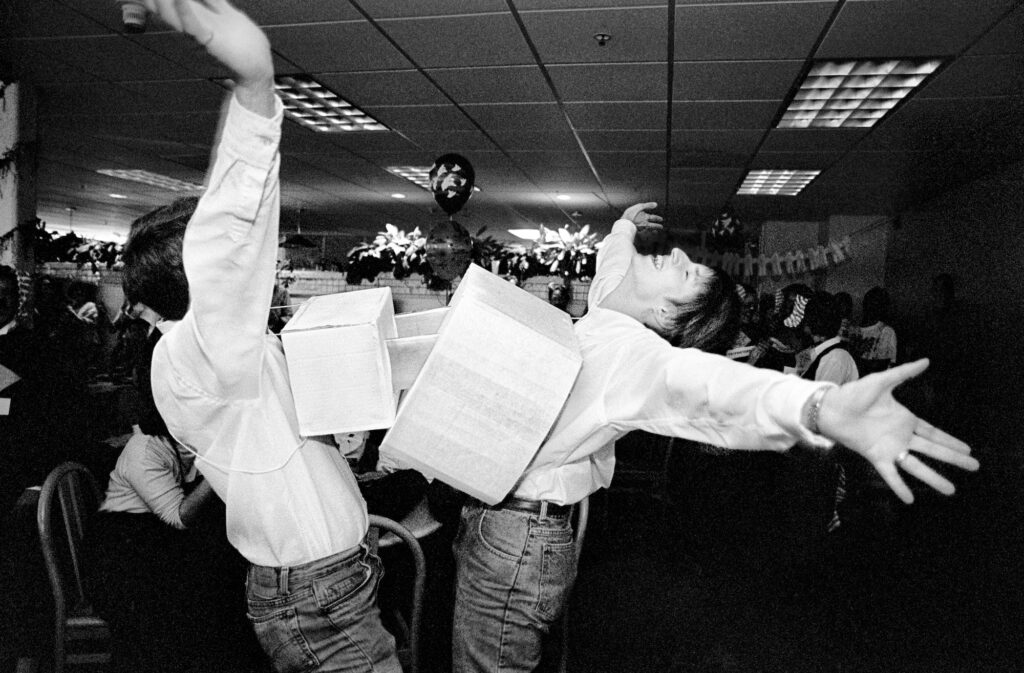

“Geek Sex.” Mountain View, California, 1991. © Doug Menuez/Contour by Getty Images/Stanford University Libraries

The title Fearless Genius refers to those I observed who had true intellectual genius, usually in math or science, or a kind of genius, combined with a rare ability to fearlessly pursue the power of their ideas to fruition or failure, risking everything they had—their health, sanity, families, jobs—in the process. All wore their workaholic, hundred-hour weeks as a badge of honor; no sacrifice was too high to “change everything.” Marriages dissolved, mothers raised their babies in the labs they never left, programmers went insane, and one young programmer I knew committed suicide. Some went to jail for fraud, others had lives ruined by collapsing companies, and a few died in flaming car crashes. And billions of dollars were made. The tremendous human cost of new technology development was not well understood.

“The Day Ross Perot Gave Steve Jobs $20 Million.” Fremont, California, 1986. © Doug Menuez/Contour by Getty Images/Stanford University Libraries

By 1999, the early idealism I witnessed turned to unsustainable greed and the dot-com bubble began to collapse. It was the end of a singular era, marked as much by technical breakthroughs as the shift from strong “we want to change the world” idealism to making money. Everything became centered around shares and cashing in on IPOs for companies with products not yet profitable, or in some cases that did not even exist. As the passion to invent gave way to a vague cynicism, I decided to end my project and put my negatives in storage. In 2004, Stanford University Library acquired my archive. While this work can never be definitive, my journey through the Valley coincided with a pivotal age, and includes almost every significant leader. To date, approximately 7,000 images have been scanned, from which the selection of images presented in the Computer History Museum’s exhibit were chosen. After I retouched the files, they were output to digital negatives and printed by hand on traditional silver gelatin paper.

I want to foster a dialog around what lessons can be learned from the era I documented. Since 2000, there has not been a single technology innovation in the United States that has scaled up to create millions of jobs as personal computers did. Facebook, Twitter, Google, and others combined have added only 50,000 jobs and are basically software iterations built on work done in the digital revolution. Creating jobs is a global issue. But here in the US the economy is hollowed out, and our education system seems broken. We’ve graduated with fewer doctorates in computer science this year than 1970. We’ve also cut visas for foreign workers and students, further limiting our ability to innovate. Kids today cannot imagine a world without texting, e-mail, or life online. They embrace all the newest digital technology but don’t understand where it came from. How can we inspire the next generation of engineers and innovators?

Who will be the next Steve Jobs?

Where will she come from?

Beneath the vast enterprise and all the PR hype I saw through my project, I discovered the joyful, primal urge to invent tools that has driven human progress for millennia. I saw something uncontrollable, hungry and wild—something human—that yet remains in Silicon Valley, with hope for a new technology revolution that can fulfill the promises of the last one.

Fearless Genius: The Digital Revolution in Silicon Valley, 1985–2000 will be on display at the Computer History Museum from July 9 to September 7, 2014.

This exhibit is made possible through the generosity of Micron Technology.

![]()