In the beginning the net was mostly non-commercial, but that began to change as it grew in leaps and bounds. Soon millions around the nation had online access, at home and at work, and the stage was set. The first money-making sites were, of course, about personals ads and about sex. But then entrepreneurs began to launch sites with information about everything from stock market data to the weather, and soon you could do your banking online, and buy and sell things, and chat. Early entrepreneurs began to get rich, and online newspapers heralded the start of the cyber age while also worrying about the future of print.

Geeks hoped that the net might be adapted to a revolutionary new computer Apple had released just months before, called "Macintosh."

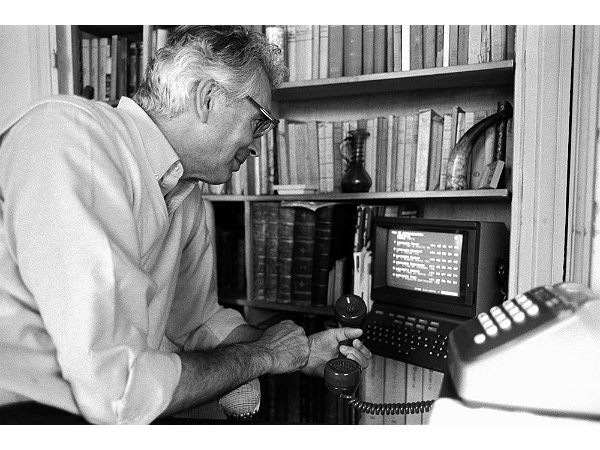

Provided by the telephone company for free, these compact Minitel terminals fit neatly on a bookshelf–unlike the boxy PCs starting to populate North American homes in the same period. © Owen Franken/Corbis

The year was 1984. The nation was France, and the net was Minitel, then four years old. It operated until last spring. There were no clickable links, and images were a bit pixelly even by 1980s standards. But Minitel offered some conveniences that could still make Web users wistful today. One was centralized micropayments; any charges you incurred online were sent out like your regular phone bill, and you only paid for the information you used, in increments down to pennies. No minimum charges or separate PayPal accounts; no worrying about phishing or being scammed. Because it cost something to send messages, Minitel users weren’t deluged with spam. There were few equivalents to browser incompatibilities, or missing plug-ins, or glitches with your cable modem or DSL. The system just worked. And yes, eventually you could surf Minitel from your Macintosh.

Minitel was the biggest of the “webs before the Web”, a full dress rehearsal with six million users by 1984 and around 30 million – half of France’s population – at its high water mark in the ‘90s. But there were dozens of such online systems, from CompuServe in North America to the nearly complete online world of the PLATO education platform. Each was somewhat different, and understanding these alternate scenarios for how to organize life online is one of the few guides to possible futures for our own.

Most early online systems including Minitel were self-contained; so-called “walled gardens” where users of one system had little access to any other. While this feudalism limited their utility at the time and created the hunger for a single standard like the Web, it also made such walled gardens near-perfect as experiments, and today as case studies. Each is an alternate scenario for how to create and use “cyberspace”, as it was termed then; a fresh start with new users free of preconceptions from other systems.

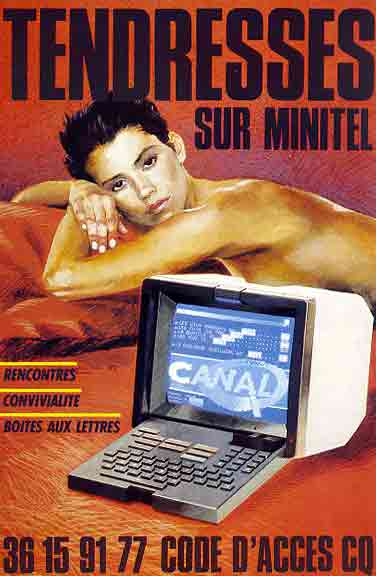

The results could be quite different. For instance, CompuServe generated most of its content from users, like social networks today. But as a corporation it had absolute power over any content it didn’t approve of. Minitel relied more heavily on professional content, from magazines to restaurant guides. But as a public utility, its owner France Telecom had to respect freedom of speech – hence the explosion of highly profitable erotic sites.

You can learn more about Minitel and many other online systems in the Web gallery of our permanent exhibition “Revolution: The First 2000 Years of Computing“.

Creating an exhibit is stressful and surprisingly hard, but it’s ultimately cheerful work. You’re sharing knowledge that fascinates you, trying with colleagues to brainstorm the best ways to both educate and entertain. But there’s a grimmer kind of effort behind the scenes. The attempt to help preserve meaningful records of online systems can feel like at best you’re managing to pull a few tomes from a library burning in slow motion.

Since early 2009 the CHM Internet History Program has been trying to collect some of the more vulnerable records of Minitel, as well as encouraging other institutions to preserve them. Such records include software, data, internal documents and other kinds of “behind the scenes” materials, the things most at risk because they tend to get thrown out. Often the people who control their disposition have no inkling they might be of historical value, or that anybody collects them.

Erotic Minitel services like this one advertised here were a major moneymaker.

I’ve formed a kind of “tag team” on this effort with Zilog pioneer and CHM trustee Bernard Peuto. He spends part of his time in his native France, and my wife and I visit family in Europe most every year. Over a series of visits, we managed to collect enough materials for the Minitel coverage in “Revolution.” We built wonderful contacts with leading historians including Pierre Mounier-Kuhn and Michel Atten, and with Internet pioneer Louis Pouzin and several Minitel pioneers in different domains. But in our visits we never quite got face to face with the people who control major archives of software and records.

Then Minitel shut down last spring, turning the constant background risk of lost records into a potential crisis. From a preservation point of view this is a high-stakes period, when much can be thrown away – or saved.

Despite Minitel and other major innovations like the CYCLADES network that helped develop the Internet, France has no major public museum with explicit responsibility for computing. But this may be about to change. Last summer, two principals of a serious effort to do exactly that – Isabelle Astic and Pierre Paradinas visited CHM. There is a very real hope that within a few years France may assemble a world-class museum of computing within the Conservatoire national des arts et métiers (CNAM), and that key records of Minitel will find a proper, permanent home. CNAM stands roughly for Conservatory of Industrial Arts and Crafts. It traces its roots back to the emphasis on technical and scientific pursuits that was part of the French Revolution, and to Encyclopedists including Denis Diderot. Its museum serves as France’s national museum of science and technology.

Insert caption here..

On my last visit to Paris in the fall, followed by Bernard Peuto’s, there were reasons to be cautiously optimistic about preserving meaningful records of Minitel. With the system’s shutdown and the new computing museum potentially in the offing, there seems to be more momentum toward saving Minitel materials. Simply by expressing interest in it as a computing museum and one with an Internet History Program, we hope we are sending a strong message about its historical importance. We talked with a number of top pioneers, computer historians and institutions about working together toward these goals. Nothing is certain, but we will keep you posted in this blog.

In the late night shared office outside Geneva, Sheryl Crow’s “Tuesday Night Supper Club” was playing for what seemed like the thousandth time; in any case enough that while I like the music, it still seems instantly over-familiar almost two decades later. Jacques, business partner of Web pioneer Jean-François Groff, was the Crowe fan.

Under the direction of a veteran Swiss TV journalist we were all frantically producing a daily, bilingual “many-media” magazine with partners including Le Monde, The Economist Group, The Guardian and Swiss TV and radio. I was Executive Editor, and the commercial Web was so new that simply combining text with video and sound online was a cutting-edge experiment for us and our partners. Just a few months before I had begun researching the Web’s tumultuous history at its birthplace, CERN, the giant physics laboratory a mile or so further out of town at the French border.

To me, the Web was one of those rare quantum leaps of newness and simplicity, where all the old, messy, half-functional predecessors get swept away in a kind of cathartic spring cleaning. The original Macintosh had felt the same way, sleekly erasing crusted years worth of memories of cranky DOS and CP/M commands and clattering impact printers.

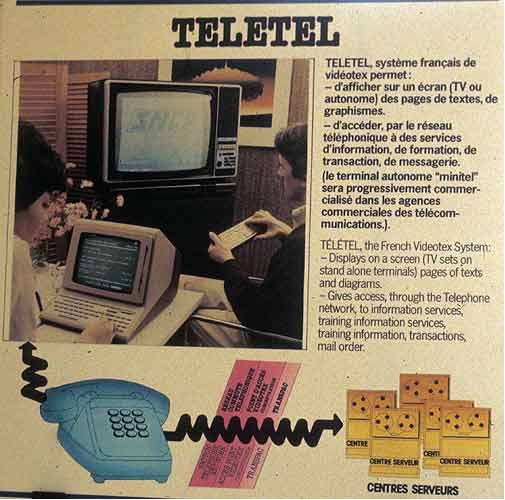

Magazine ad, 1982. Officially the service was called “Teletel,” and the free home terminals were called “Minitels.” But the latter name stuck.

I’d been vaguely curious about Minitel, the French online system, but hadn’t done more than briefly play with it. The simple interface and quaint little terminals lumped it more in my mind with text-based BBSs like The Well or the closed, commercial world of CompuServe than this newly world-wide, shiny Web.

But on some of those late “Supper Club” nights Jacques told me more about Minitel. Before he and original Web programmer Groff had founded InfoDesign, the first Web services firm, Jacques had worked for several years on the mostly unsuccessful efforts to extend a Minitel-like service to Switzerland.

To him, everybody else’s bright new Web felt like mostly a retread. It had slicker graphics than Minitel, sure, but was still in a very primitive stage in terms of the sorts of services offered, integration into people’s lives, e-commerce, and more. He said many of the new kinds of Web startups he saw gave him a sense of déjà vu, and he could sometimes predict which models would work based on how their predecessors had fared on Minitel. E-commerce, and the rise and fall of geek entrepreneurs, were nothing new. Jacques was in his 30s, a quietly self-assured young businessman with a wry smile. But when it came to the online world he was an old timer, watching youthful follies with a jaundiced eye.

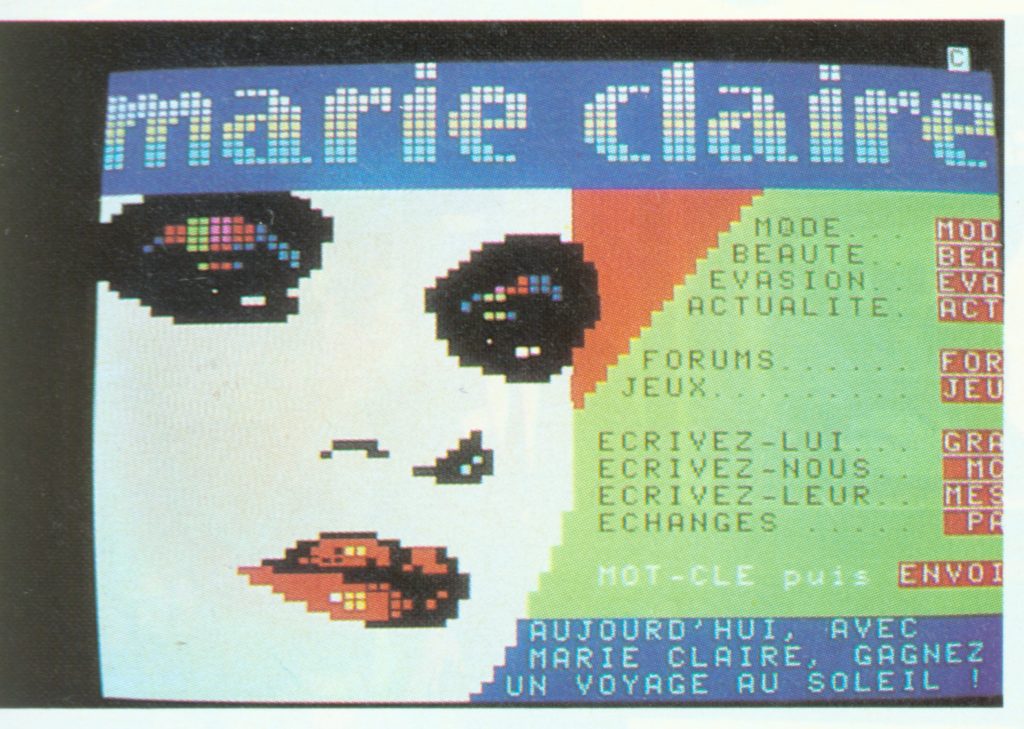

Minitel hosted some of the first truly mass-market experiments in online publishing. Shown here is an online issue of the women’s magazine Marie Claire.

It also turned out that our experiments in online journalism weren’t quite as bleeding edge as they’d seemed. While Minitel lacked video, many French newspapers and magazines had been online and interactive – with graphics – for up to 15 years. In fact, back at the system’s development phase in the late 1970s, the traditional media’s fear of being extinguished by new “e-media” had been a major obstacle. Had the newspapers won, Minitel might not have been built at all.

Most of the people who helped invent and build out the Web at the start of the 1990s had experience with other online systems. Some had even built systems of their own. But as that era recedes in time, the first hand knowledge goes with it.

In science, and economics, and business and politics and even fashion, we routinely scour the past. We look for comparison points, forgotten innovations, and lessons learned (or not). Will we manage to preserve meaningful records of early online worlds? Only then can we hope that future researchers and entrepreneurs will have the chance to learn from the triumphs and the mistakes of the “webs” that came before.

The Museum’s Internet History Program collects material on the evolution of computer networking including the Web, the internet, and mobile data. The first of its kind at a major institution, the Program covers networking as both a technical invention and a new kind of mass medium. Founding curator Marc Weber has researched the history of the Web since 1995, and co-founded two of the early organizations in the field.

The exhibit face of the Program includes the Web, Networking, and Mobile Computing galleries within the permanent “Revolution” exhibition. Together, these galleries form the first major exhibit on the origins of our online world. All of the content in the physical galleries is also available in the online versions. The upcoming “Make Software: Change the World” exhibit will highlight the social impact of software, much of it online. An updated and expanded timeline exhibit will also further chronicle the evolution of the networked world. The temporary exhibit “Going Places: The History of Google Maps with Street View” traces the history of “surrogate travel” back to 1970s computer systems and before.