The Vintage Computer Festival attracted exhibitors from around the world, including Oscar Vermeulen of Walchwil, Switzerland, with his retro-computer replicas. Photo by Erik Klein

The 2016 Vintage Computer Festival (VCF), an amazing grass-roots showcase of historical computers, was held at the Computer History Museum (CHM) on the weekend of August 6 and 7. VCF has a rich history that makes for intriguing commentary about the preservation versus presentation of historical objects and is a favorite event among computer enthusiasts everywhere with new standout exhibits each year.

Started in 1997 by Bay Area entrepreneur Sellam Ismail, VCF has been held in various Silicon Valley locations (including CHM) through 2007, with spin-off festivals on the East Coast and in Europe. After a nine-year hiatus on the West Coast, the festival was resurrected in 2016, led by a new group—the Vintage Computer Federation—spearheaded by Evan Koblentz, with CHM volunteer and docent Eric Klein serving as producer. Several components have always been part of VCF in its various iterations, most notably its speaker series, consignment market, and exhibit displays. This year was no different.

Early Apple employee Daniel Kottke with the Apple-1 computer on display at VCF. Photo by Jeff Brace

Over the years, speakers, ranging from Steve Wozniak to Gordon Bell to Lee Felsenstein, have regaled gathered crowds with stories of their careers. This year, a panel featuring three of the most significant figures in early computer gaming was the highlight of the final day of the festival. Steve Russell, best known for his work co-designing the game -Spacewar! for the DEC PDP-1 minicomputer. Al Alcorn, designer of Atari’s PONG, and Don Woods, writer of the original game Adventure, spoke of gaming’s early days and the challenges of creating and playing games presented at the time.

Perhaps this year’s most anticipated talk was given by Silicon Valley engineer and businessman Bob Zeidman. One of the long-standing questions of early PC operating systems has been over the authorship of QDOS, the operating system purchased by Microsoft. QDOS served as the basis for its industry-standard MS-DOS operating system, introduced in 1981. CP/M’s inventor, the late Gary Kildall, had claimed that his OS had been illegally copied to create QDOS, and thus Microsoft’s entire operating system business was based on fraud. This led to a standing grudge between several factions. Zeidman’s team investigated the claim, examining source code for both CP/M and MS-DOS. Deep forensic analysis showed no direct connection between the programs.

Another popular attraction since the festival’s beginning is the consignment market where hobbyists sell their retro-tech to fellow hobbyists. One of the most impressive pieces I saw this year was a “Topo” robot from Nolan Bushnell’s robotics company Androbot. This robot, only briefly on the market, was 3 feet tall and represented a period of the 1980s when many toy companies saw robots as the “next big thing” in home entertainment.

The highlight of VCF is always the exhibitors, many of whom travel thousands of miles (even crossing oceans) to attend and set up their displays. These die-hard hobbyists from around the world bring mainframes, minicomputers, microcomputers, analog computers, software, and peripherals to every festival. It is also through the exhibits that we see the divide between the museum ideal of preservation and the hobbyist’s desire for interactivity.

The collection of Tomy Tutor computers, peripherals, and software. Photo by Evan Koblentz

In museum and computer-collecting communities there is a conflict about which is more important: preservation or presentation? Most museums argue that to use objects is to hasten their loss to the world. By contrast, hobbyists often point to the idea that to maintain these objects but not present them for use as they were intended is to allow them to become static objects, concealing the intricacies and contexts of their function. Both of these two collecting philosophies were seen in the various types of exhibits at this year’s VCF.

There were some amazing and historic pieces, like collections of rare computers from Japan or Cameron Kaiser’s collection of Tomy Tutor devices and games. Jim Stephens and Sherman Foy, from Orange County, California, brought several items relating to minicomputers from Digital Equipment Corporation and Microdata. Highlighting front panels from both companies, Stephens also displayed a lovely Honeywell 440 mainframe front panel, which may be the only example still in existence.

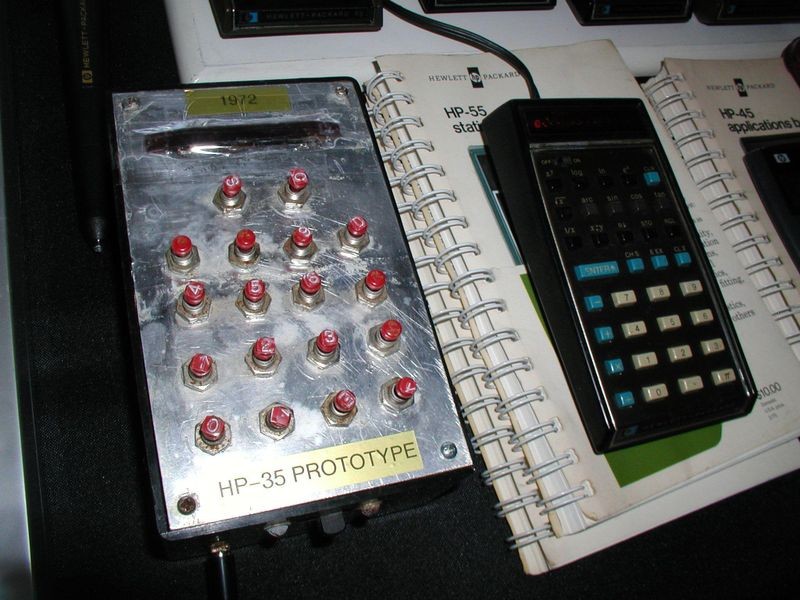

To me, the most important piece was a one-of-a-kind device. Former Hewlett-Packard marketer Don Apte brought the original prototype for the legendary HP-35 electronic calculator. While barely able to be held in a single hand, and looking nothing like the finished product from 1972, the HP-35 prototype was a metal box with small red buttons and a simple display. From the point of view of a curator who has a deep interest in early electronic calculators, this piece was an absolute highlight of VCF for me. These items represented typical museum ideology, preserving artifacts and displaying them . . . even if the exhibitors didn’t wear white cotton gloves when they showed the pieces off.

The HP-35 Prototype, a one-of-a-kind display from Don Apte. Photo by Bill Degnan

On the other end of the spectrum, the interactive exhibits were impressive. Vintage PCs ran games like Adventure, and a lovely display on the early work of Video Toaster inventor Tim Jenison allowed attendees to interact with a video digitizer and MacPaint-inspired CoCoMax, both running on a Tandy-Radio Shack Color Computer.

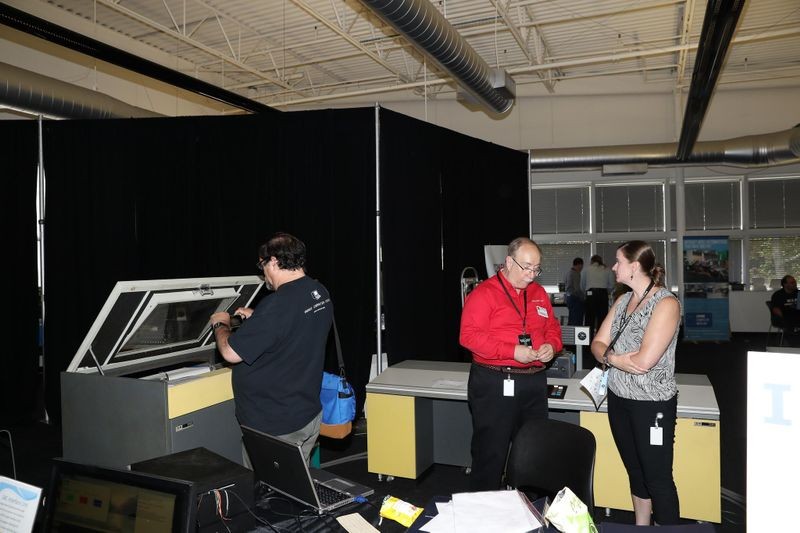

The use of these original pieces raises questions for museum professionals. CHM has sponsored restorations of some machines, including the DEC PDP-1 and both IBM 1620 and 1401 computer systems, and these restorations are extensively documented and must adhere to strict rules of restoration for any changes that are made. Exhibiting at VCF was the Museum of Art and Digital Entertainment (MADE) in Oakland, California. Known for preserving original, playable equipment, as well as performing restorations, MADE brought several systems for guests to enjoy. A museum of electronic games may well say the value of a game is in playing it, but over time, how much damage is caused by running these systems?

The Living Computer Museum in Seattle brought a small-networked system, allowing visitors to play the early first-person shooter game MazeWar! Running on modern hardware the experience might not be exactly the same as when MazeWar! first ran on the IMLACs at NASA Ames Research Center, but the emulated experience allowed attendees to feel close to the original, with less expense and potential damage to antique hardware. Another form of emulation on display at VCF were replicas. Oscar Vermeulen of Switzerland sells replicas of machines like the DEC PDP-11 and the KIM-1, using modern parts; Bill Buzbee’s Magic-1 homebrew CPU was a new design using TTL chips; and Steve Chamberlin created the “Big Mess o’ Wires,” an original, handmade 8-bit CPU concept.

Eric Schlaepfer demonstrates his MOnSter6502 processor. Photo by Erik Klein

While using modern components to simulate older varieties is often the norm in restoration work, one impressive exhibit went in the other direction. Eric Schlaepfer’s MOnSter6502 is a transistor-for-transistor replica of the MOS Technologies 6502 microprocessor used in millions of computers, including the legendary Apple II and BBC Micro. Using 3,218 surface-mount transistors, 1,019 resistors, plus LEDs that show the status of various control lines and registers, the MOnSter6502 re-imagines the original microprocessor, but at a lower speed, greater power consumption, and roughly seven thousand times larger than the original. While these devices might not be “authentic,” as those of us involved in museums might see them, they allow an experience that at least approximates those had by users in a bygone era. The ability to interact with these devices allows historic hardware to be maintained, remaining out of touch and held precious, while still giving the visitor an experience that comes close. Some hobbyists see this negatively, that attempting to subvert the use of original hardware makes the interaction false. It’s not standing in front of the Mona Lisa; it’s standing in front of a knock-off print. The experiences are not equal.

Tim Robinson explains his Meccano Differential Analyzer to a vistor. Photo by Erik Klein

The work of Tim Robinson makes an interesting case for both the preservation and the presentation sides of the argument. Working with Meccano, a mechanical British construction toy using metal strips, gears, wheels, and connectors, Robinson has created a number of interpretations of vintage technology, including portions of Babbage’s Difference and Analytical Engines. This year, Robinson displayed a computer Differential Analyser. Historically, Meccano had been used to create analysers in the 1930s and ’40s, most notably at Cambridge University. Robinson created his analyser using four mechanical integrators consisting of gears and wheels turning on glass disks. While not the largest display, its complexity and impressive layout, made it a favorite of attendees and judges alike, but it was also a showpiece, operating under a strict “No Touching” policy. It is a recreation, but its authenticity lay in the thorough documentation and its creation, using the kind of parts that might have been used in the 1930s and ’40s. The value of this kind of re-creation is in the ability of the visitor to witness the workings of the machine without compromising an original device.

The twin IBM 1130s – the original on the right, a well-crafted replica on the left. Photo by Erik Klein

To me, the most impressive piece was Carl Claunch’s reproduction of the IBM 1130 computer system, not only emulating the computing experience with modern hardware, but also emulating the physical experience by creating a full-scale replica of IBM’s original. Claunch exhibited the recreation alongside the original, and due to the painstakingly precise work done with the cabinetry, at first glance, I thought they were simply two vintage machines. Claunch created a full-size cabinet and connections for peripherals, while the logic for the computer was contained in a small box within it, forcing the user to deal with the same physical limitations as those who would have worked on the 1130 in the 1970s. This certainly showed the two kinds of retro-computing aficionado at the same time—the preservationist and the demonstrator.

Solid-State Monopoly, a long-running project by Steve Casner. Photo by Evan Koblentz

The role of events like VCF in the ecosystem of retro-technology enthusiasts can’t be overstated. They are gathering places for enthusiasts, each with a different desire in their interactions. There is value in both strict preservation and direct access to retro-technology, and understanding how they can interact, to further both long-term preservation and interactive recovery of the context of use. Such collaborations can only help to illuminate the history of computers for everyone.