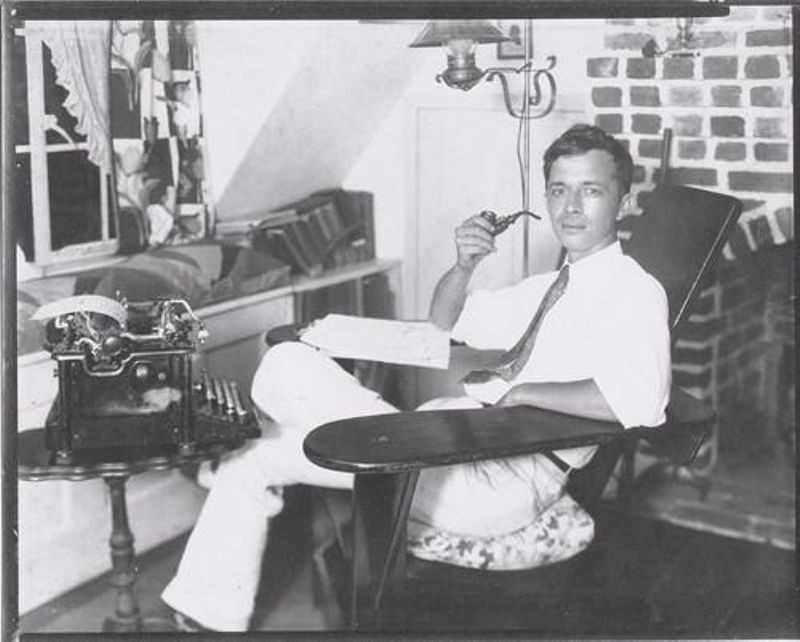

Will F. Jenkins (aka Murray Leinster) in his home study, 1930s. Used with permission of the Literary Estate of Murray Leinster.

How much influence have television, movies, literature and art had on the sciences?

We get a glimpse of many future technogies from science fiction. While it’s difficult to find direct influences of science fiction on technology, it is much easier to find examples of those who first fell in love with science through fiction.

I’m fascinated by the so called “lucky guesses.” Some call it prognostication, but few writers and artists were trying to predict what the future will be. Mostly, they were trying to tell stories about universal themes, like our dependance on our tools and the specter of losing control to them. One story that managed to see further down the line than most, is a story from 1946 that seems to have understood the times we live in today: A Logic Named Joe, by Will F. Jenkins (aka Murray Leinster).

Excerpt:

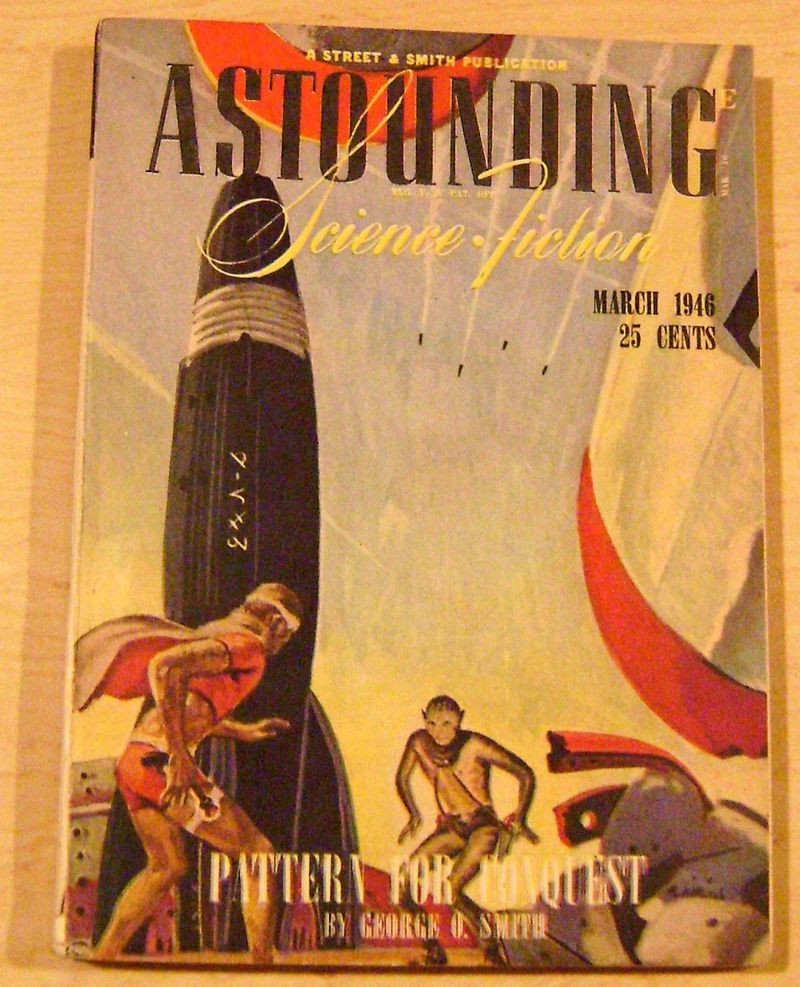

Astounding Science Fiction, March 1946 from the collection of Bradford Lyau

In the March 1946 issue of Astounding Science Fiction, then the leading science fiction magazine for the day, Will F. Jenkins, better known under the pen name Murray Leinster, published the story A Logic Named Joe. The story featured a ‘logic’, a device similar to today’s personal computers, which starts to alter the way information is available on the ‘Tank,’ a network of audio-visual and information resources. The logic allows access to what are typically restricted materials, allowing users to search for dangerous and private information.

Joe, the central device of the story, has a simple malfunction that allows him to access circuits and optimize his own operations. The logics in the story allow users to access not only information, but also television programs and place person-to-person phone calls. The Tanks are large data servers, each holding information on data plates.

Sounds a lot like the personal computers and internet we know today, doesn’t it?

There are significant differences, though. The logics and machines of the Tank are made of relays, the kind of switches used in telephone equipment and early computers. These were slow and large components and while they were the fastest kinds of devices available at the time, they would not have been fast enough to perform work at great speeds and without great cost. Data plates also seem to be the kinds of disk platters that were invented in the 1950s with systems like IBM’s RAMAC hard disk drive, though there’s little detail about them. It’s likely that Jenkins had little first-hand knowledge of work going on in computing at the time, though perhaps he was aware of some of the reporting of work by people like Vannevar Bush that had been covered in the popular press.

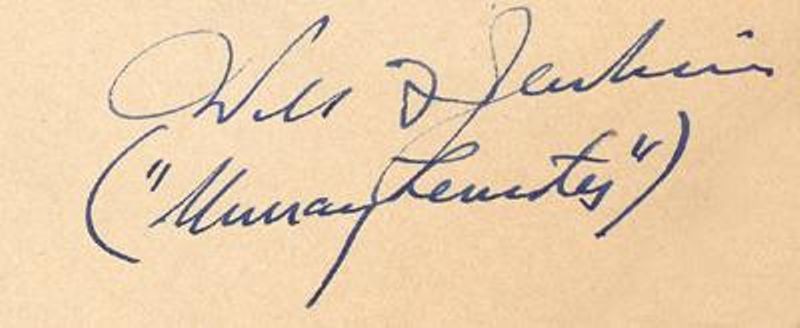

Autograph of Will F. Jenkins (and Murray Leinster), courtesy of Michael Krakoviskiy

Jenkins writing career stretched from 1916 to 1974. He wrote science fiction and fantasy stories as early as 1919, and by the 1940s was already seen as one of the most adored authors of the genre. His first important science fiction story, The Runaway Skyscraper, appeared in the legendary pulp magazine Argosy in 1919. Jenkins also wrote hundreds of westerns, mysteries, romances and science fiction stories, most often under the pseudonym Murray Leinster, but also under his real name and as William Fitzgerald. In particular, Jenkins is noted as the first writer to work in the vein of ‘parallel worlds’, including one of the most influential pieces of science fiction written in the 1930s, Sidewise in Time. Not only did he write novels and stories, but he was a prolific screenwriter and scriptwriter for radio dramas and television. His work straddled the period of the greatest change in the field of science fiction, and his stories and scripts formed the basis for much of the science fiction that would be written in the 1950s and 60s, when Leinster would be seen as ‘The Dean of Science Fiction.’

He was also an inventor who had a laboratory in his home and held several patents. His most impressive work of innovation was improving and patenting a front projection system for use in filming special effects. Front projection would be used in many films, with one of the first and most notable being by Stanley Kubrick in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Excerpt:

A Logic Named Joe features the title character computer “Joe” over-riding the ‘censor-circuits’ and making information deemed damaging available for viewing by anyone who asks to see it. This includes information on how to commit the perfect murder, how to rob a bank, make a perpetual motion machine and other scientific inquiries.

What information a person should have access to, is one of the prime concerns of those interested in internet advocacy. Many argue that all information should be freely accessible, while others believe that access to certain types of information can be very dangerous. Unlike in A Logic Named Joe, there is no single entity that owns the internet and can truly control what people have access to. Software designed to shield children from inappropriate content has been available nearly as long as the World Wide Web has been in existence. Several countries have used systems to ban specific websites from being accessed by their citizens. This has led to discussion about free speech and how much power a government can have over accessing information from other nations.

Science fiction authors have used the idea of centralized and decentralized networks, and control over them, as the basis for stories ever since tales like A Logic Named Joe first appeared. The Cyberpunk movement of the 1980s and 90s was based around questions of network access, governmental control and power.

Excerpt:

A Logic Named Joe is one of the first stories to describe a machine that could be considered a personal computer. The logics perform tasks that most computers today do routinely, including playing entertainment videos and providing homework help.

The personal computer was developed in the 1970s following fast on the heels of the invention of the microprocessor, twenty-five years after the article was written. As prices for microprocessors, monitors and other components came down, more people were able to afford computers. By 1995, many home had computers in them.

The internet began life as the Arpanet in 1969, a research network designed to share information between different groups. Unlike ‘the Tank’ in A Logic Named Joe, the Arpanet was a de-centralized network, meaning that there was no single machine that all computers were connected to, but thousands of ‘nodes’ which were all interconnected. The World Wide Web, introduced by CERN researchers in the early 1990s, was adopted in many parts of the world as a quick way to spread information and communicate with one another.

Today, more than a billion people use the Internet for everything from shopping to research. Few, if any, individuals saw this wave of information processing coming in the 1940s, as electronic digital computing was in its infancy. What makes A Logic Named Joe so fascinating is not just what he got uncannily right, but how much Jenkins understood about people and the way they interact with machines. The logics in Jenkins stories are essential to the lives of the characters every bit as much as computers and the internet are to people today.

The story, written almost twenty-five years prior to the invention of the personal computer, and even before the wide-scale availability of televisions, is considered one of the most prescient of all science fiction stories. While many earlier writers had mentioned possible computers, none understood the power they would have over the day-to-day lives of the average user. Imagine a time when the most advanced computers required hours of difficult set-up to run a single problem, and when the typical input method was either card or tape. Individual processes could take hours, sometimes days, and there were no commercial computers yet on the market. The only people who actually used the machines were academics and researchers. Imagine convincing someone from that time, that they would not only own a computer, but that they would personally be able to access vast libraries of information through it.

A Logic Named Joe is truly astounding science fiction.