CHM’s Squee, The Robot Squirrel is on display in Revolution: The First 2,000 Years of Computing. CHM # B1630.01

On October 9, CHM was privileged to have as a special visitor, Mr. Jack Koff. Koff built one of CHM’s more interesting and early robotic artifacts—Squee: the Robot Squirrel. Squee was the idea of early computing popularizer Edmund Berkeley. Berkeley began working as an actuary for Prudential Insurance but quickly rose to prominence for two reasons: one, he co-founded the Association for Computing Machinery in 1947, still the world’s leading body for computer science professionals; and secondly, he wrote the hugely popular book Giant Brains or Machines That Think (1949). Two years later, in Radio-Electronics magazine, Berkeley published plans for what is perhaps the world’s first personal computer, Simon.

Simon is in CHM’s permanent collection and is on display in our major exhibition Revolution: The First 2,000 Years of Computing. Simon was based on relay logic (129 relays) and, as Jack Koff noted in his visit, most of the parts used were from the vibrant WWII surplus shops on Canal Street in New York City. Described as a ‘mechanical brain,’ Berkeley envisaged many people building Simon-like machines:

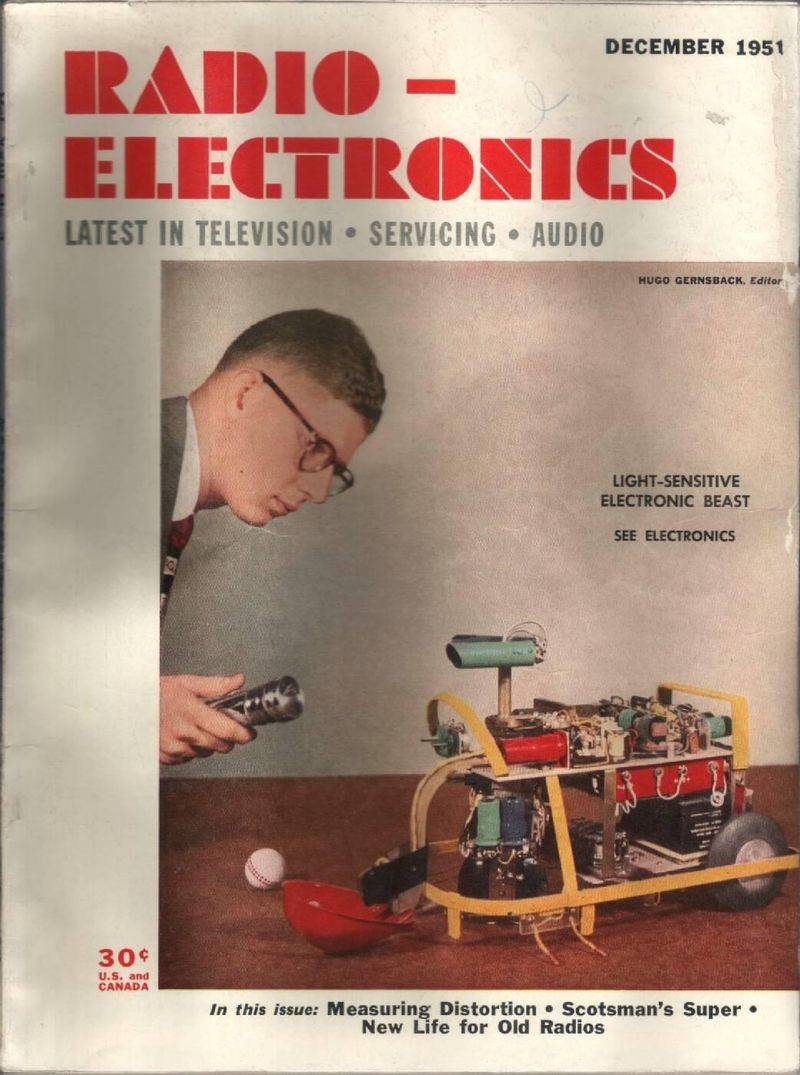

Jack Koff with Squee on the cover of Radio-Electronics magazine, December 1951

It is unknown how many Simons were built, but it was an ambitious construction project and by 1959, over 400 plans had been sold. The first one was built by two electrical engineering graduate students at Columbia University.

Squee, The Robot Squirrel, was the featured construction project on the cover of the December, 1951 issue of Radio-Electronics. Jack Koff was one of three assistants Berkeley hired. As Koff recalls:

CHM’s Squee “has been modified quite a bit,” Koff notes, although the 60-year old yellow paint Koff himself applied still looks good. Squee owed an intellectual debt to a similar series of robot—called ‘turtles,’ known as Machina speculatrix, (but nicknamed Elmer and Elsie) and developed by British neuroscientist Grey Walter in 1948-49. Berkeley wanted to emulate Walter’s robots and describes how Squee worked:

Squee (named after “squirrel”) is an electronic robot squirrel. It contains four sense organs (two phototubes, two contact switches), three acting organs (a drive motor, a steering motor, and a motor which opens and closes the scoop or “hands”), and a small brain of half a dozen relays. It will hunt for a “nut”. The “nut” is a tennis ball designated by a member of the audience who steadily holds a flashlight above the ball, pointing the light at Squee. Then Squee approaches, picks up the “nut” in its “hands” (the scoop), stops paying attention to the steady light, sees instead a light that goes on and off 120 times a second shining over its “nest”, takes the “nut” to its “nest”, there leaves the nuts, and then returns to hunting more “nuts”. When Squee is operating, it is a dramatic and exciting example of a robot. It has been exhibited in New York, Pittsburgh, and Minneapolis, and has always entertained and excited the audience. The machine however is sensitive to the surrounding light level, and usually has to be shown in a room about 8 by 10 ft. with only a small amount of overhead light and black curtained walls. Data: completed; rather well finished but not professionally; 75% reliable; maintenance, difficult; our costs, about $3,000. [1].

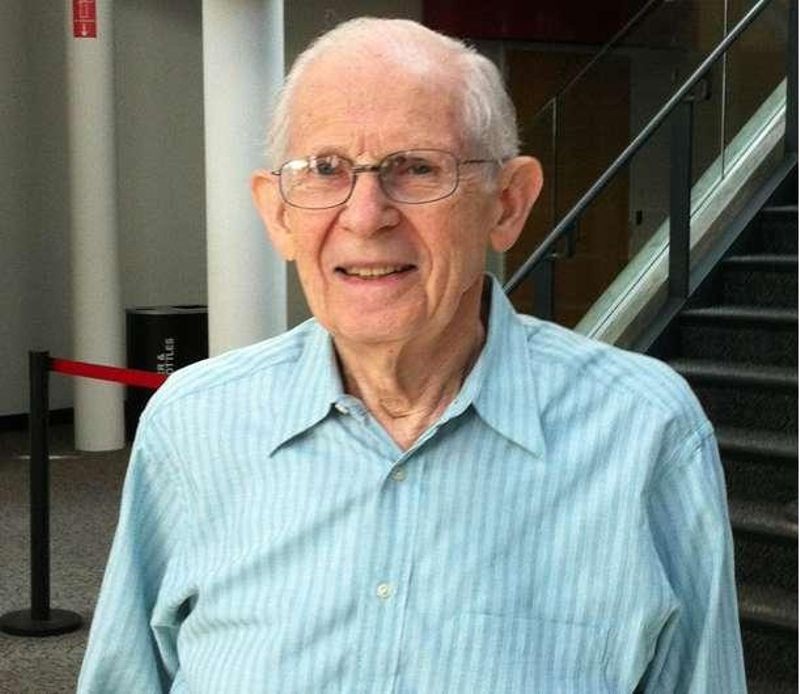

Jack Koff, original Squee builder, visits CHM on October 9th, 2012

Koff, 21 years old, exhibited both Simon and Squee at the Minnesota State Fair in 1951 for The Dayton Company (now Target).

The demonstrations were a success, although Jack had to obtain a number of extra batteries as Squee would only work for 15-20 minutes on a single charge.

As Koff notes, however, CHM’s Squee now has its head backwards—the two ‘eyes’ (photocells) are pointing to the rear instead of forward. We plan to rotate the photocells in the near future.

What did people think of robots at the time?

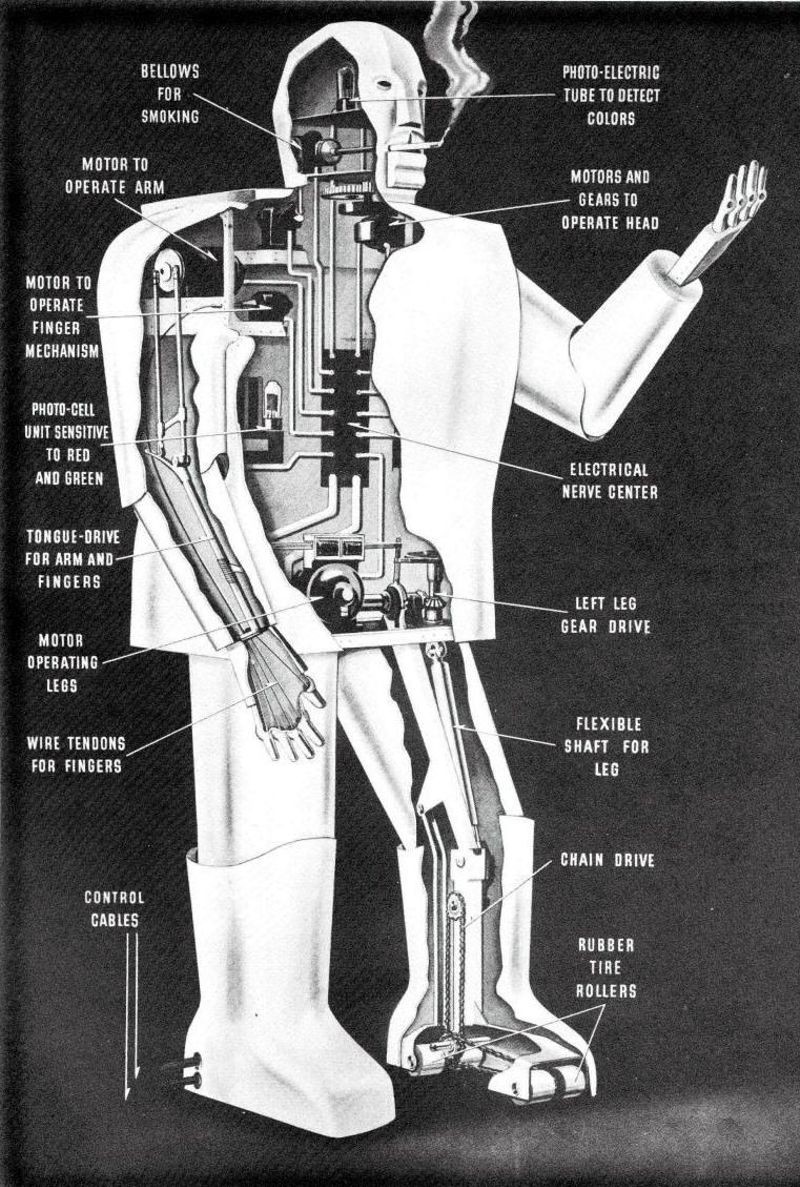

Elektro was a gaint 7 foot tall remotely-controlled humanoid robot that could say 700 words, smoke, blow up balloons and move his head and arms. The next year, “Sparko,” the robot dog appeared and he could bark, sit and beg. Clearly Squee is part of this tradition of animating animals and people using electromechnical technology. From the earliest days of robotics, people have been delighted, afraid and intrigued by robots. Squee was one of the first.

[1] Berkeley, Edmund C., Small Robots – Report, Berkeley Enterprises, Inc., April, 1956, 815 Washington St., Newtonville 60, Mass.

Westinghouse’s “Elektro” robot at the 1939 World’s Fair

Inside view of Westinghouse’s “Elektro” robot at the 1939 World’s Fair