1952 US Presidential Election campaign poster featuring Eisenhower and Nixon as the Republican ticket.

The year 2012 marks another step in a familiar quadrennial cycle. A cycle culminating in an event that demands global attention and that has people in awe of the amount of effort and money spent to ensure that the competitors reach their peak with meticulous timing. I am not talking about the 2012 Summer Olympic Games held in London this year; I am talking about the 2012 United States presidential elections. While the pageantry is quite different in style, the inescapable media onslaught and mind-boggling expenditures associated with both events do compare.

Many sports appear easily quantifiable: times, heights and lengths, and weights – following the old Olympic motto Citius, Altius, Fortius. And of course goals, baskets, or a myriad of other terms used to describe one team scoring over another team in many sports. Anybody who has watched the Olympic Games for any period of time can tell a story of when some competitor was robbed, usually in a sport that relies on points awarded by subjective judging. Frequently this incident is followed by an outburst of thinly veiled nationalistic media furor and extensive debate amongst people who suddenly know how much a horse should move during the piaffe in dressage, where a diver’s pike position went wrong, or (as this seems especially popular during the Winter Olympics) whose skater’s triple Axel was subpar.

The scoring of sports and the tallying of votes follow specific rules, well documented, enshrined in laws of their respective bodies. While in the former case the outcome of the event has limited effect, in the latter it may tip the scales on the state of the planet in one way or another. In theory elections should be, as the simile goes, an absolutely quantifiable horserace and not a subjectively judged dressage event. For a non-voting resident alien like myself, it is a mesmerizing display, albeit one anticipated with some trepidation, when the results roll in on election day and the mathematics begin their circuitous route through the anachronistic Electoral College before finally settling on the next President of the United States of America.

Surely, the American teenager at the verge of the age of suffrage is equally dumbfounded by the U.S. electoral system as was this German by the method employed in my home country. In light of this, and the generally low level of numeracy of the body politic, the vast numbers of polls, projections, and surveys dominating the airwaves in the weeks and months leading up to the presidential elections are entrancing. It isn’t clear that the analogy to sports still holds when it comes to polling, but when looking at the ranking system of college athletics in the United States or the industry of sports betting, one wonders if there is maybe a deeper fascination by American society with the perceived predictive power of numbers.

This brings us to the main story: the use of a UNIVAC computer by CBS for forecasting the results of the 1952 U.S. presidential election. The immediate post-War years of the United States brought the baby boom and economic expansion; it also brought the Korean War, McCarthyism, and an increase in tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union (by jessica). President Truman decided not to run for another term in the face of unpopularity and the Democratic Party nominated Governor of Illinois Adlai Stevenson for president. The Republican Party, following bitter, internal wrangling, nominated popular World War II general Dwight Eisenhower; Richard Nixon served as vice presidential candidate.

Between the 1948 and the 1952 elections, a shift in American mass media started to take hold. Whereas in 1948 most voters would have heard results over the radio, televisions began to enter households in larger numbers in the 1950s. Television was dominated by the big three networks, CBS, NBC, and ABC, all three deeply rooted in radio broadcasting both for their news as well as entertainment programs. Television was the new frontier for mass media and the public was captivated by it. Whether it was useful as a medium to disseminate news was still unclear however and even veteran newscasters like CBS’s Edward R. Murrow were uncertain how the transition from radio to television could be achieved.

Computing burst into popular culture with UNIVAC (Universal Automatic Computer) in 1951, arguably the first computer to become a household name.

Ever more advanced products and technologies seemed to define the experience of the American consumer. The computer was at the pinnacle of high tech. This was a time when the number of large-scale electronic computers installed in the country was still in the single digits and Remington Rand seized the opportunity to introduce themselves to America as the maker of UNIVAC – the computer system whose name would become synonymous with computer in the 1950s. Remington Rand was already widely known as the company that made the Remington typewriters. The company bought out the struggling Eckert-Mauchly Computer Corporation in 1950. Pres Eckert and John Mauchly had led the ENIAC project and then embarked on making a commercially available computer, UNIVAC.

When ENIAC was declassified in 1946, it made the front page of the New York Times. MIT’s Whirlwind computer was featured on Edward R. Murrow’s See It Now newsmagazine television show in 1951. The 1952 election coverage provided something quite different; whereas computers had previously appeared as instruments of science and research, UNIVAC could be shown as a useful, although extremely expensive, commercial product.

Political opinion polling has a long history in the United States and most people are familiar with the Gallup organization. George Gallup gained fame by correctly predicting Franklin Roosevelt’s win in 1936, but also garnered negative attention when incorrectly predicting a Dewey win over Truman in 1948. This was in line with prevailing opinion and the photograph of Harry Truman holding up the Chicago Daily Tribune declaring “Dewey Defeats Truman” is legendary.

In light of this, it seems that it would have been prudent of CBS to be cautious in how to approach using UNIVAC in the 1952 election night broadcast. Remington Rand also had a lot to lose if the machine’s predictions turned out wrong. In CBS’s New York studios, newsman Charles Collingwood manned a mock-up console of the UNIVAC computer. The actual machine was at Remington Rand’s UNIVAC division in Philadelphia. The system that had been commandeered for the effort was designated to be shipped to the Atomic Energy Commission’s lab in Livermore, California.

UNIVAC received very little airtime. After Charles Collingwood introduced the “fabulous electronic machine,” he struggled to describe its operation and components. Items new to the viewer were presented in familiar and unthreatening terms: “See those round things over there, looks kind of like candy mints? Well, those are reels of metallic tape.” When it was time for UNIVAC to shine, Collingwood anthropomorphized the machine: “Have you got a prediction for us, UNIVAC?” UNIVAC did not answer.

Preparing for CBS to use a UNIVAC in its 1952 election coverage, UNIVAC designer J. Presper (“Pres”) Eckert and operator Harold Sweeney show the machine to American news icon Walter Cronkite.

The resulting dead air that strikes fear into any broadcaster’s heart was filled with banter between Collingwood and election night anchor Walter Cronkite. Over the course of the night, on a few occasions the two tried to engage UNIVAC again, with largely the same results. What must have seemed odd to the viewer, even though they likely sympathized with the newsmen’s opinion about how the machine isn’t making humans obsolete just yet, wasn’t actually caused by inaction on the part of UNIVAC.

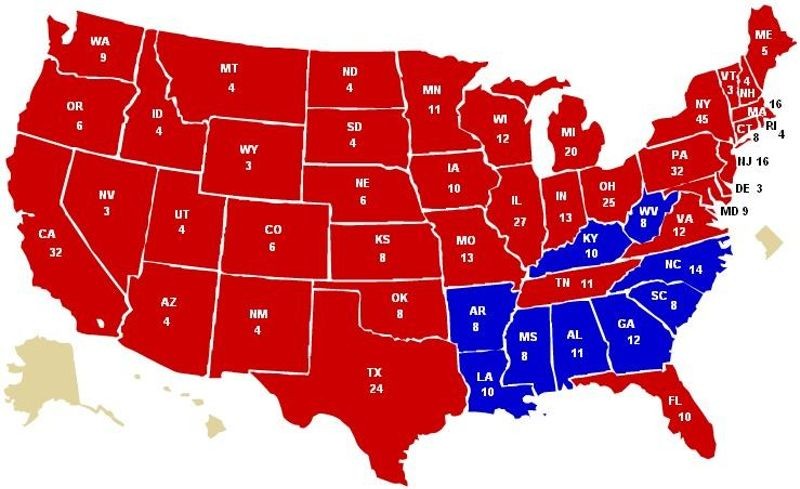

1952 US Presidential Election Dwight D. Eisenhower (Republican), Electoral Votes – 442, Popular Votes – 33,778,963 Adlai Stevenson (Democratic), Electoral Votes – 89, Popular Votes – 27,314,992

The statistical models that had been programmed and calculated, did predict the outcome of the elections early and correctly. Counter to the commonly held view, Eisenhower was winning by a landslide! In an early printout, when the odds for Eisenhower’s victory were 100 to 1, the three digits necessary to display were truncated – the programmer’s didn’t expect either candidate to be favored that strongly. In the end, the Eisenhower/Nixon ticket won handily and repeated that feat even more resoundingly in 1956, again against Stevenson.

It isn’t clear if Remington Rand or CBS held back the predictions, but Remington Rand representative Art Draper came on the air after midnight: “As more votes came in, the odds came back and it was obviously evident that we should have had the nerve enough to believe the machine in the first place. It was right. We were wrong. Next year we’ll believe it.”

Both NBC and ABC also used computing devices during the 1952 election. But the use of UNIVAC, a much larger, more powerful machine, struck a chord with the public. Remington Rand’s UNIVAC division sponsored TV broadcasts. Newscasters as well as comedians made reference to UNIVAC for years to come. The news media didn’t necessarily embrace computing technology following this display. It took some more election cycles before computer models became a fixture on election night.

The situation in 2012 is quite different from 60 years ago. Multiple 24-hour news channels, constantly updating Web sites, and a barrage of information streams arriving through social networks vie for attention. The number of data sources for pundits and analysts to pore over has also magnified greatly. Interestingly, some of the prognoses were exactly on point, no doubt due to better statistical modeling techniques. A number of other ones were vastly off base, but received just as much attention, amplified in ideological echo chambers. In the end, the distrust in the projections has not really fundamentally changed from 1952 – no matter how sophisticated the models, how eye-catching the computer generated graphics. It struck me as an interesting parallel to CBS’s (or was it Remington-Rand’s?) uncertainty of 60 years ago when Fox News questioned their own projections of President Obama winning in the state of Ohio. Conservative pundit Karl Rove called the prediction premature and the Fox News team scrambled to get a response from their Decision Desk. The pollsters were comfortably confident with their predictions and stuck with their initial call, which turned out to be correct.

In the end, the 2012 elections reaffirmed the status quo of U.S. politics at the national level. The polls, the predictions, all the statistics are the livelihood of the news media during election cycles. The seasoned observer chooses to pay little attention to many of these numbers, because in the end it all comes down to tallying the votes. The race is over, there is a winner. The horserace has been run and all the subjective judging of polls comes to an end on election night. The news media will continue to make hay of the results as long as possible. Elections are a race, but politics really are dressage.